Rob Daviau is a tabletop game designer responsible for some fairly well-known board games. You might be familiar with his haunted-house twist on cooperative games, Betrayal at House on the Hill, or his contributions to the miniature-based war game Heroscape. But far and away, his most well-known achievement is the Legacy system.

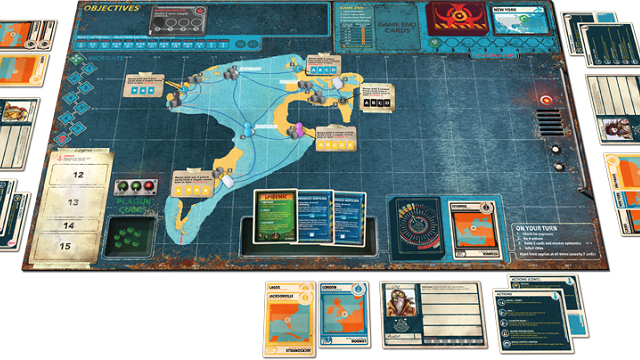

So far consisting of Risk Legacy, Pandemic Legacy: Season 1, and SeaFall, the system boils down to a basic principle — after a game is completed, it doesn’t fully reset. Instead, elements of previous games carry over to future sessions in the form of stickers you place on the board, secret compartments within the box that contain new mechanics that open when certain criteria is met, and even ripping up cards. It can be difficult to have a continuous campaign, as it more or less requires a consistent gaming group, but if you’re able to pull it off, it can make for some really unique fun.

Daviau currently has numerous new games in the works, including a sequel to Pandemic Legacy, and he was able to find time in his schedule to let us ask him a few questions.

GameSkinny: Do you remember how you first had the idea for Legacy?

Rob Daviau: (laughs) Yeah, I get asked this a lot. The short version is that it was just a brainstorm at Hasbro about Clue, and it was a combination of a joke that I made, about how they shouldn’t keep inviting these people over to dinner because they keep murdering people — along with sometime in the same hour — and I don’t remember exactly when we were brainstorming and I was looking at assumptions that games have, and how to turn them on their head. And I said, “What if the game didn’t fully start over each time? What if it had some sort of memory of what happened before?” And in some sort of combination between that joke and that comment, we came up with the idea.

GS: So objectively, your most popular game is Pandemic Legacy: Season 1. It’s been sitting at #1 on BoardGameGeek for what feels like ages at this point.

RD: Yeah, a year and a half. Which is a short run to be at #1 there. So we’ll see how long it lasts.

GS: I believe Season 2 has been coming along in the background, and so, without giving away spoilers for those who haven’t had a chance to play through the first one, what has it been like to work on what’s essentially a sequel to a board game? And will there be options to have experiences with the first game carry over to the new one?

RD: So I finished Season 2 about a year ago. So it has been translated into different languages during that time, proper art [has been] done, production, manufacturing… Because of the success of Season 1, it had a big production run here, which is great, but it’s just took a long time to get all the games because I wanted them to come out at the same time, because Legacy games can be, or have spoilers… They didn’t want to do some here, some there, you know, trickle in.

I started the sequel before the first one came out. The game was going to come out in October of 2015, and we started Season 2 at the beginning, or April, of 2015. So there’s this weird cycle of starting before the other one comes out.

So the good news is we had no idea how successful it was going to be, so we weren’t sort of constrained or crippled or otherwise affected by its success when we started Season 2. And in many ways it was great because we had tried to figure out in Season 1, how a Legacy game would work as a cooperative game, and how it would work specifically in Pandemic, and we had already done a lot of that work and didn’t have to reinvent the wheel there. What we did have to do is say, okay, we did all these cool things in Season 1; how do we not just do the same thing again in Season 2? So it was like pushing ourselves to come up with whole new ideas.

In answer to the second part of your question, there is no mechanical connection between Season 1 and Season 2. Season 2 takes place 71 years into the future. Because of the different end states of Season 1, and we didn’t know at the time how many people would finish on a high note or a low note, there’s a lot of variables about how a player’s world can look at the end of Season 1. And so we made the decision to just move it — sort of reunite the timelines, I guess. By moving it 71 years into the future you can say, okay, these people did these things, but — and I’m not gonna spoil it — then something else happened, and then you all sort of ended up in the same place.

And I know that’s a disappointment to some people who wanted it to fully connect, but we were trying to figure out — the variable end states would have left dozens, if not hundreds, of places we would have to pick up from and all have it work, and that was a bit of a difficult matrix.

GS: Yeah, makes sense. Is there any idea of a tentative release window, or is it still too early to tell?

RD: It’s going to be in the fall. The reason — and I keep meaning to email and ask if they have a specific date yet, at least behind the scenes — because the game has all sorts of complexity with scratch-off materials and stickers and scoring and collation and pack-out, and because of the high print volume, they really didn’t know how long it was going to take to do it. And so if they said, okay, it’s going to be, make up a term, August 31, and then there’s 10 days of delays in production because some glue isn’t drying because of the humidity in China, that presents a huge problem. So I think they’re waiting for the games to be done and on a ship and maybe even cleared customs in all countries before they turn around and say, okay — so it’s gonna be a pretty short window. I think they’re gonna say, like, one month from now or three weeks from now, when that comes. I would expect it to be — they’ve said fall, so my mind’s September, October timeframe.

GS: The Legacy system has been pretty successful, to the extent that other designers have also tried their hands at making Legacy games with that system. Do you have any thoughts on that?

RD: Well, it’s flattering. There have been a number of games that have [been] very close cousins to what I’m doing, which is the nature of things. Like, “I like it but I want to do it my way.” So you have a game like [Fabled] Fruit, which is a card game that picks up where you left off, but there’s nothing permanent. You could always start over. You have games like Gloomhaven, which has been wildly successful, which has Legacy campaign elements, but in a very different way than what I’m doing. It’s much lighter, the Legacy elements. There is a Netrunner campaign game, I think, that has some stickers and rule changes, but I don’t play Netrunner, so I haven’t played that game. If there’s others I’m missing, I would like to know because I’d like to sit down and play — I mean there’s the Escape Room games that have all come out this year that I know are inspired by escape rooms, but also are sort of one-time consumable puzzle games, so maybe were inspired by Legacy as well, hard to say. But I haven’t played one that’s sort of really close to the types of things I’ve been designing. But I’m hoping to.

GS: Well, my next question was going to be if there were any favorites that weren’t made by you, but you kind of answered that I guess.

RD: Well, I’m looking for one where people come out and say, ‘This is something Legacy’, like 80% of what I did. I feel like the other ones are more like 40%, so they’re cool. T.I.M.E Stories kind of did the same thing but it’s a little different. It’s fun to sort of have these one-off experiences in games, where the designers can make them– they can control the experience more, because they don’t have to deal with infinite replayability.

GS: Looking back at your three big Legacy titles — Risk, Pandemic, and SeaFall last year — what are some ideas that you hit on that you think have worked especially well? And is there anything you wish you’d done differently?

RD: There’s a couple things in all of those games that I would do differently, to various degrees. Well, maybe not Risk, interestingly enough, just because it was the first one and so it was just a crazy mishmash of ideas. There’s some little things, I feel like there’s a couple rules that weren’t that great, I would change what I call the triggers to two of the envelopes to open in a different order. Like, I really want this to open before this one most of the time.

Pandemic, Matt [Leacock] and I messed up both conceptually and executionally something — when you’re about 2/3 of the way through the game, if you’re sort of falling behind and we want to get you back on track, we have a little way to do [that] ,so that’s sort of clumsy in concept and clumsy in execution, that justifiably we get some criticism for. Also we did some weird numbering mistakes. Like we have the big packages that you open, and there’s eight of them numbered one to eight. And then the dossier doors also start over at one to eight, so you don’t necessarily know which number to open. In Season 2, the packages are one to eight, and then the dossier starts with 10. There’s no duplication of numbers.

SeaFall I really like, but the feedback has been that it needed another round of development. I think it had taken so long that the publisher and myself were — I was done. I couldn’t figure out any way to do anything new with it and I thought it was perfect. The publisher knew I wanted it out the door and they just kind of put it out the door, and I think looking back now, I can certainly say, ‘Oh, I wish that one of us had said hold on, give us six months to play it and chop it and make some edits on it.’ So that one was so big and so sprawling and I was trying to grow a business at the same time that it both consumed my time and didn’t have enough time, ironically. So, you know, there’s always things in games I’ve worked on that once they’re out and you get feedback or you just get some time on it, you say, oh, okay, I could have done that differently. I think that’s just the nature of it.

GS: And things that you think worked especially well?

RD: Well, the whole concept of permanently making change and having a campaign, the very conceit itself seems to have struck a chord. Which was a complete shock to me when Risk came out. Like, I thought there would be a few really crazy role playing gamers or something who would get into it.

I think the story we ended up putting in Pandemic Legacy resonated with people, which is interesting because it takes place over the course of something like 18 cards. There’s very little that we tell you about the story, and it’s just interesting how people put together the story. There’s a hidden packet in Risk Legacy that I still continue to enjoy, and that was so whimsical that I don’t know when or if I’ll ever do that again. There’s something that people who get like 2/3 of the way through SeaFall and open a packet — there’s a little trick in there that I also particularly like that I’m being coy about, that I think is great and fits narratively and people have really had sort of a jaw-dropping moment for it.

So yeah, it’s weird. Some of the things that I think of for Legacy games are not necessarily just game design ideas but experience ideas, almost like magic tricks. What if we hid something? What if we hid something in plain sight? These sorts of things. I’m happy to be able to think that way when thinking about a game.

GS: What do you see as the future of the Legacy system? Do you see a sort of future or a way you want to evolve it?

RD: I don’t know. I mean, they take a lot of time. And I’m working on a number right now, but in my head, I’m not gonna take on too many more right now, because I would love to work on some things that are a little smaller and a little easier. And I suspect like any trend in gaming, books, music, food, that people will be like, ‘Okay, I’ve had enough of that, now I want this over here’. And so I don’t think it’ll go away. I think it’ll have its little curve and go down, like deckbuilders or something. I don’t think it’s gonna be the type of thing that’s all I’m making, where I’m making three a year for the next 10 years. I’d be surprised if that happened. If that happens, great, but that would be surprising.

GS: Before we wrap up, next month, you’re dipping into Lovecraft a bit with the release of Mountains of Madness. From the premise, it almost sounds like a sort of Betrayal at House on the Hill setup, where it starts out fully cooperative, but your teammates slowly get crazier and crazier as you progress. Can you speak to any similarities or differences between the two?

RD: Well, there are more differences than similarities, and that’s one of the interesting things about this. No one becomes a traitor in this game, and there’s no hidden traitor. The game is entirely cooperative, but the players, all of them in various ways, become more and more inefficient at being cooperative due to their madnesses that they get. At its heart, it’s a communication game. I used to call it a party game but that’s not quite an accurate term.

Really, the heart of the game is all players have 30 seconds on a sand timer to communicate what they’re going to do as a group, what cards they’re going to play to deal with things, which is interesting. Some people just mess that up right out of the gate. Like, very simply, there’s a sand timer and they just panic. Because when the timer goes off you can’t talk about or clarify any plans, you just have to play the card or cards or don’t play the cards you think everyone agreed to. And then what happens is as you both succeed and fail, because it’s a Lovecraft thing, you get more and more restrictions on what you can communicate. So you might have a madness that you can only communicate with the player on your right. You do not talk to anyone else, you do not listen to anyone else, you do not hear anyone else. You start putting four people around a table, each with these various conflicting madnesses, and it becomes a real challenge to communicate effectively.

GS: So you’re challenging another board game preconception — that players will always be able to talk at will with each other.

RD: Yeah, a little bit, but this is the reason I called it a party game. Most party games do something about communication restriction. Pictionary, you can only draw. Charades you can’t talk at all. Codenames, you can only say one word and one number. So a big part of party games is restricting communication and trying to get people to understand things without the use of just being able to say it. So in some ways, this hits that party game genre, but it’s not a party game, like it’s not a wacky social game, right? Like, there’s strategy and you have to figure out when you’re gonna spend some certain chips and where you’re gonna go.

GS: Lastly, anything else you want to say to get people hyped for the game?

RD: It’s different. Like, it’s interesting, I enjoy Cthulhu, but I’m not super into the mythos. I appreciate it for what it is and I find that there’s a lot of Cthulhu games that really speak to the people who know the world, and I’ve tried to make a game that was just more accessible that happened to be a Lovecraft-Cthulhu theme. You don’t have to know all the lore and the creatures and the words and the backgrounds — essentially, it’s just an interesting communication challenge. So I think it’s a Cthulhu game for people who have been daunted by Cthulhu.

A big thank you to Rob for taking the time to answer my questions!

Here’s a link to Rob Daviau’s website. You can also check out his page on BoardGameGeek, or follow him on Twitter.

Published: Jul 27, 2017 02:05 pm